Tropical Storm Sandy formed Monday afternoon in the Southern Caribbean Sea. The storm has achieved as much hype on Twitter and Facebook in one day as some big storms get in a lifetime. I’m getting bombarded with “Storm of the Century” questions about the potential impact. There are some extreme computer model solutions out there, but there are also several reliable computer models that take the storm south of Bermuda and harmlessly out to sea.

At the risk of contributing to the hype, I’ll go hypothetical with some of the different computer model scenarios for this storm. For many, the computer model names will be nothing but a jumble of letters, but the point I’m trying to make is that there is a ton of uncertainty with this storm, and it is by no means time to even casually worry about it hitting New England.

GFS Model

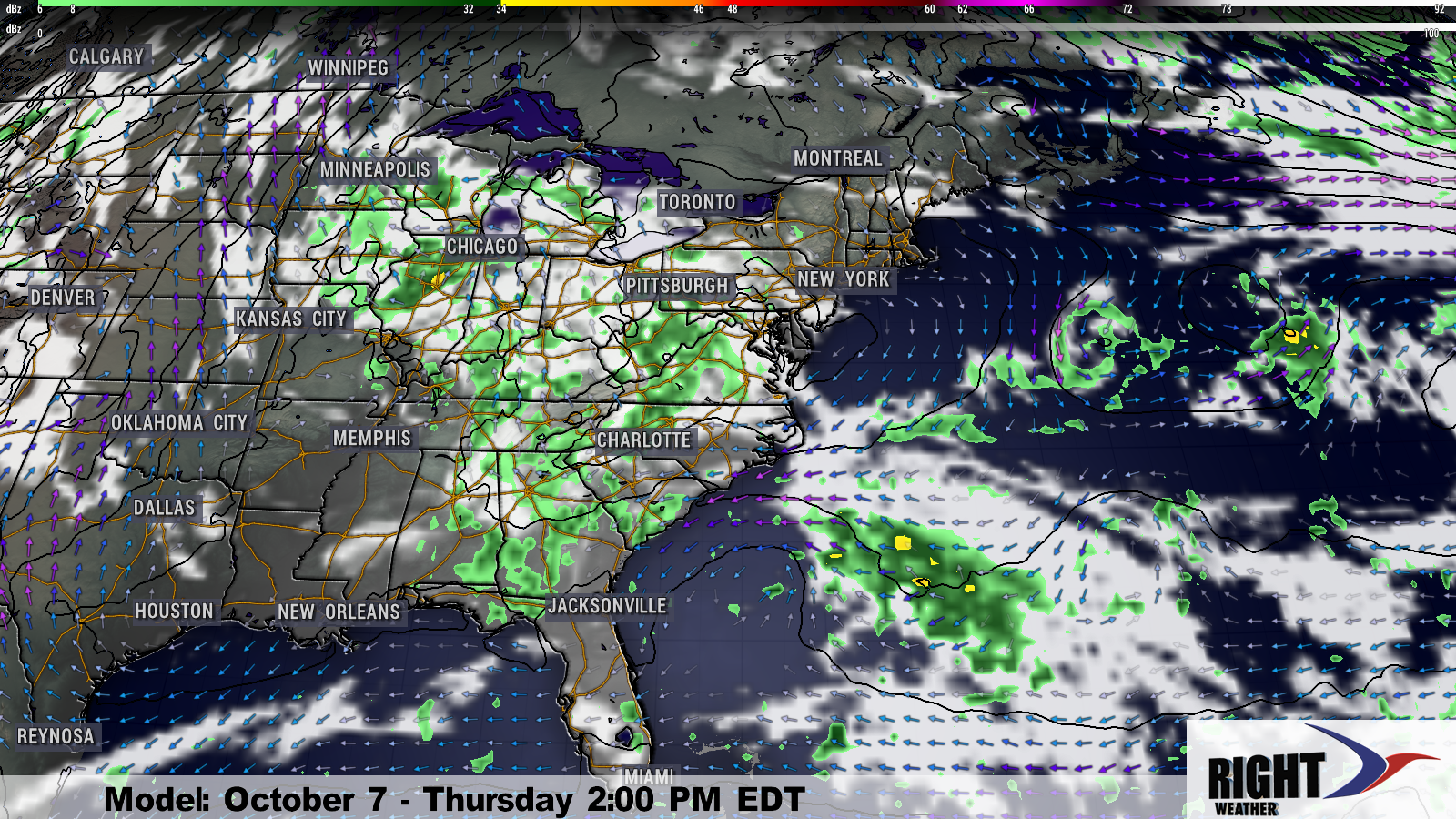

The Sunday morning run of the GFS was the match that set off the inferno of Sandy chatter. The forecast was for a storm of hurricane intensity (fig 1.) east of Atlantic City, NJ on the morning of Halloween. The GFS has since bailed on this solution, and for the past five runs (4 per day) has shown the storm going much farther east. The latest GFS (fig. 2) runs are near or south of Bermuda, and the end result in Southern New England is a fresh northerly breeze – no big deal, to say the least. Without getting too technical, one of the common complaints with those who discard the last five GFS runs is that it is jumping too much energy to the east when the storm is near the Bahamas, and as a result the rest of the simulation allows the storm to slide harmlessly out to sea.

ECMWF Model

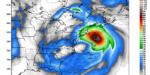

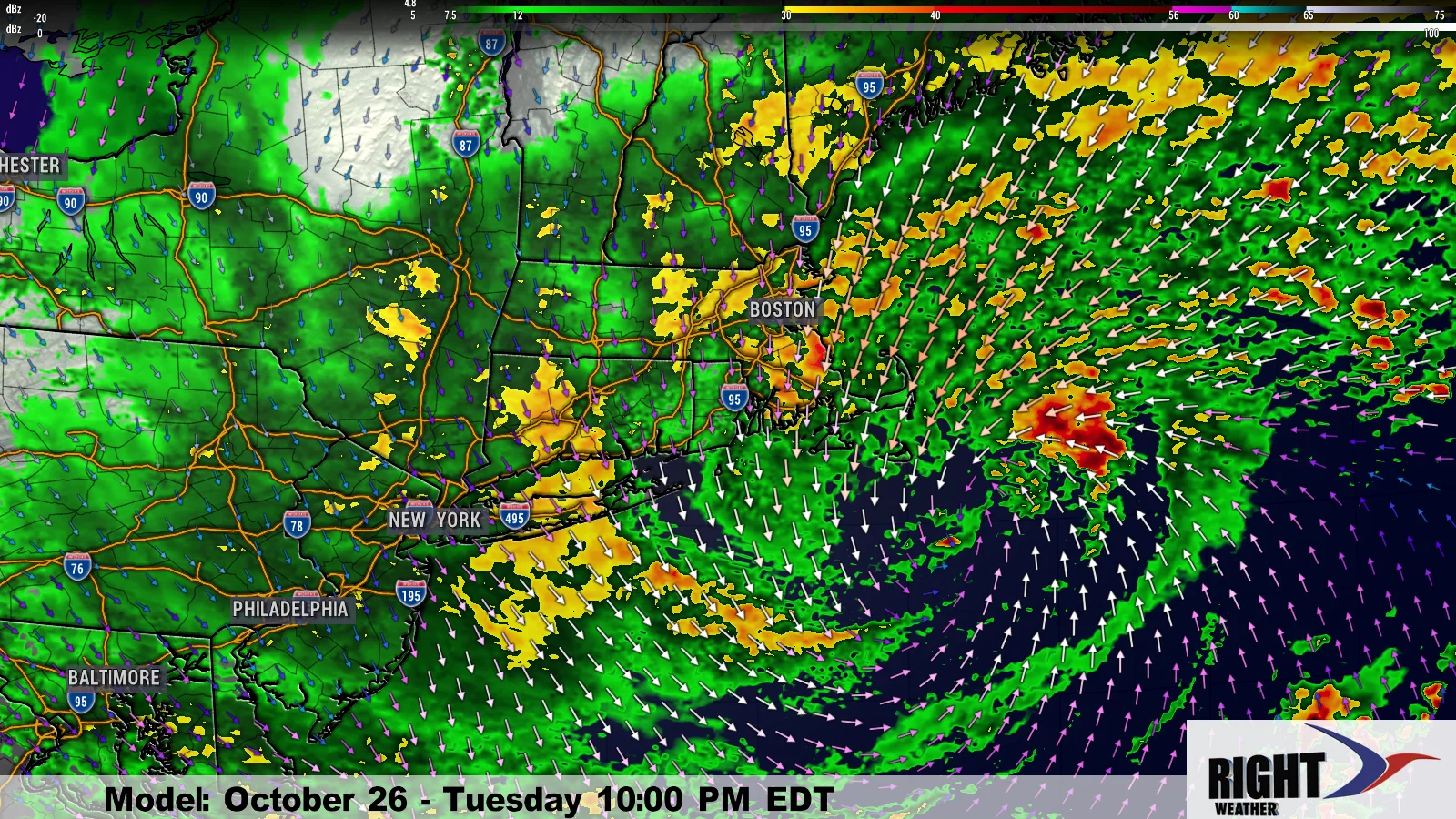

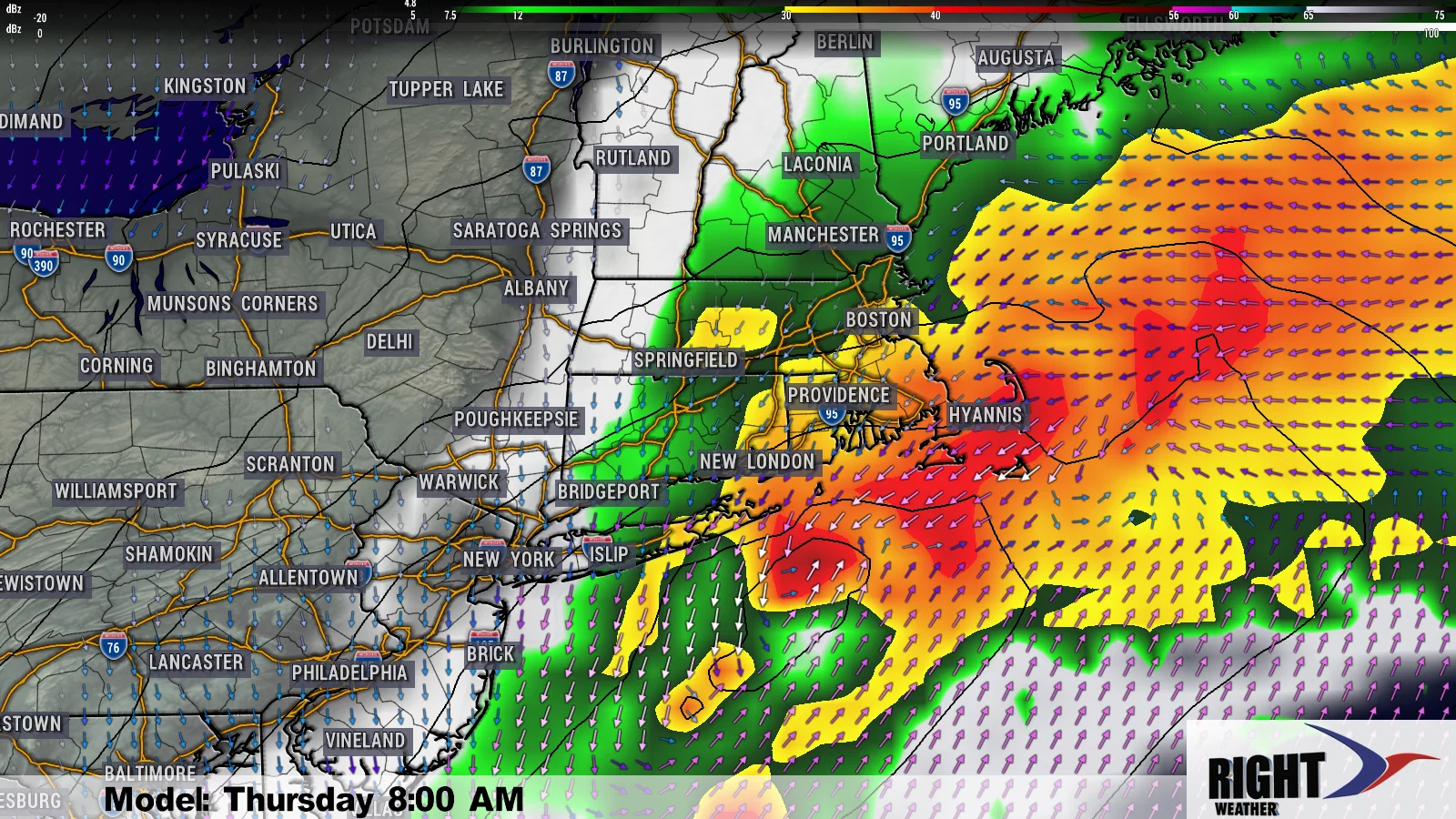

The ECMWF (European) Model has everyone talking today. First, last night’s run (fig. 3) put a menacing storm off Cape Hatteras Monday night, and then slammed it into the Mid-Atlantic Coast on Tuesday. This is a dire scenario, but Monday morning’s run upped the ante with one of the most extreme computer model projections I have ever seen. This run takes a major hurricane (Fig. 4) with a ridiculously low central pressure (927.8 mb) to south of Martha’s Vineyard on Halloween morning. The computer model then pummels Southern New England with a hybrid-hurricane storm. It’s nuts. Really, it is.

Forget about the intensity of the storm for a minute, and focus on the shift in the track from one day to the next. The ECMWF has shifted the storm about 200 miles farther east than it’s previous track. The ECMWF Ensemble is even further east, with no landfall at all in the United States. I’m guessing you may not hear too much chatter about that on social media. Why turn down the hype machine when it’s running so smoothly?

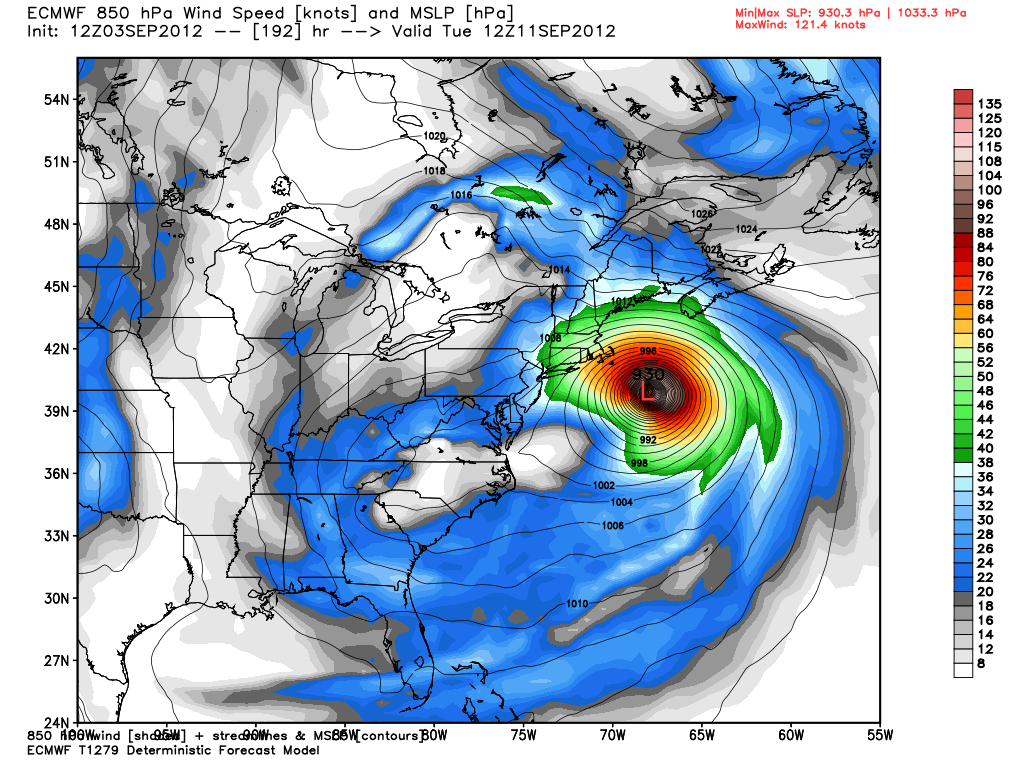

Here’s my beef with the Euro. For years, it’s been a go to model for some difficult forecasts. It has proven to be more accurate than the GFS over the long haul. Earlier this year, it was the only model that took Isaac into the Gulf of Mexico instead of east of Florida. It won by a knockout in that fight, but, let’s also not forget how it performed on Tropical Storm Leslie. The track forecast was not good, and the intensity forecast was horrendous. At one point, (fig. 5) it was calling for a 930mb near 40N/70W. Leslie was 988 mb tropical storm when it crossed 40N – at 59.1W! Therefore, I don’t have a lot of confidence in this model’s ability to be accurate with a 7-9 day forecast.

GDPS (Canadian Model)

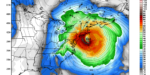

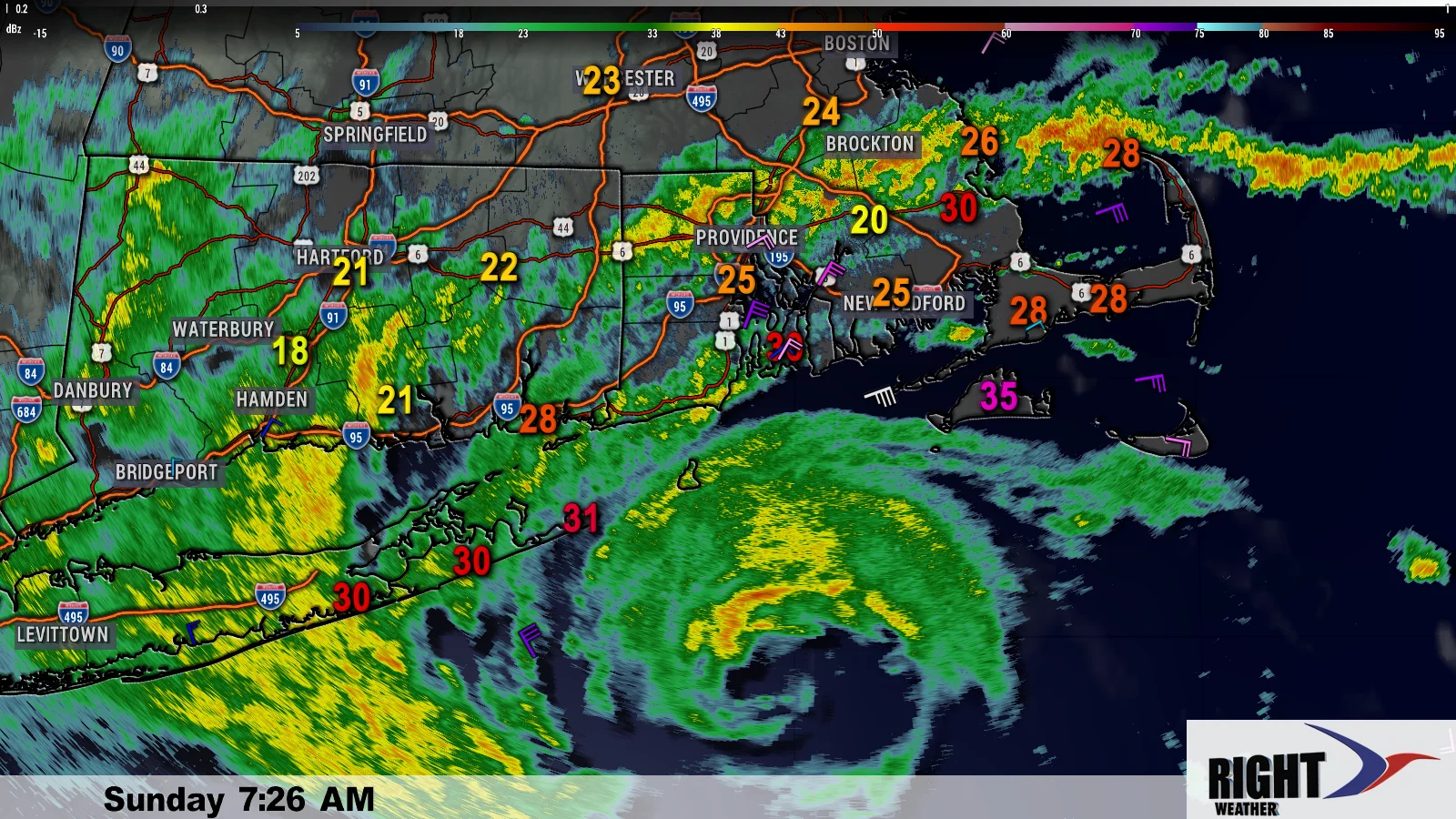

The GDPS, commonly know as the GGEM or CMC model, has been the most consistent computer model in bringing an intense, borderline-hurricane storm (fig 6 and fig 7) into the Mid-Atlantic. The only problem with the GDPS is that it has the tendency to significantly over-develop tropical systems in its mid-range forecasts. As a result, it’s also considerably faster than the other models, bringing the storm to the Mid-Atlantic coast by late this weekend. So, it’s easy to say this model has a similar solution to others (NOGAPS, ECMWF) that threaten the East Coast, but it brings the storm to the coast two days earlier. Is that really a similar solution?

Hurricane Models

While a lot of stock is being put in those models that have a major impact on the Eastern United States, I don’t know if the same credence is being given to the hurricane-specific computer models (fig. 8) which unanimously send the storm out to sea. This, combined with the climatology of late-season (Oct/Nov) tropical storms (fig. 9) in the vicinity of Sandy, heavily weight the odds in favor of a storm that does not directly strike the East Coast.

The bottom line

While I’m not comfortable saying that this storm will definitely not hit the United States, the overwhelming likelihood is that it will head out to sea. The true bottom-line for me is that we’ll not know for certain until the storm crosses Cuba and hits its crossroads in the Bahamas. It is as that point, likely late this week, that the storm will either continue to drift north or will start to turn northeast and head out to sea. When looking at Figure 8 it’s easy to see how clustered the computer models are over Jamaica and Cuba, but they diverge drastically after reach the Bahamas. Until then, all the possible solutions I outlined may stay viable. The trend, however, has been for an eastward shift in the past 24 hours, and, if I had to bet on it, I would wager on that trend continuing in the next few days.